Money – Breaking One Of Society’s Last Taboos

by Margrit Kennedy, August 2008.[1]

We all spend most of our days either earning or spending money. It is as essential to our survival as air, food and water, since in our culture hardly anyone is capable of being self-sufficient anymore. But what actually is money? Despite having known it for millenia and used it on a daily basis, there is nothing comparable of which we know so little. Do you know what money is? Where it comes from? Who is setting the rules of the game? And what does money have to do with the future of our planet?

Could our common understanding of money have led us astray into intellectual imprisonment?

One may wonder: How is it possible that all of a sudden, in a rich country like this, there can be such a pervasive lack of it? Where did all the money go that people worked so hard for over generations? Why is it that an ever greater economic growth is continuously called for as a solution to so many problems? Why is the fact being ignored, that in a finite world there can be no infinite growth? Why must all trade be “economic”, despite this being so clearly at the expense of nature and of human beings? Why are science and politics eschewing the answers to these questions?

The reason is that we are here dealing with one of the last taboos, which must be broken, if we are to survive on this planet. The present system is in the process of suffocating life on Earth by means of its exponential, i.e. cancerous growth.

In this contribution I will try to explain how the global, financial, social and ecological problems are related to the commonly accepted monetary system, how our monetary system is working, the “constructional flaw” which is preventing the development of a truly free, social and ecological market economy, and what the potential solutions might be. This constructional flaw in the monetary system allows a small elite to grow ever richer; meanwhile, the large majority – without understanding how this happens – grows increasingly poor.

Part 1: The Monetary Problem and a Solution

Causes of the need for economic growth and redistribution

Technically speaking, we could be in the position today of creating a space for humanity: we would be able to provide each human being on this planet with all that is necessary for living, and moreover let machines carry out the most disagreeable tasks. What is lacking, is money.

The permanent pressure for growth in the economy and the lack of distributive justice in our society stem from the monetary system itself.

But what is money if not an agreement among people to accept and employ a particular medium as a means of exchange, be it banknotes, coins, or as in some parts of the world – shells, and in war – cigarettes? Could our common understanding of money have led us astray into intellectual imprisonment? Upon closer inspection, there is not even a lack of money. As a matter of fact, there is plenty of it. What is in fact lacking, is a fair distribution of money, and thereby a fair distribution of access to the world’s resources. What most people do not understand is that, of the monetary transactions being carried out globally, only two percent bear on the actual exchange of services and commodities. In contrast, 98 percent of all transferred sums are employed in the domain of currency for purely speculative purposes.

My main thesis is that these conditions, which in the long run are unsustainable, as well as the permanent need for economic growth and the lacking justice in respect of distribution in our society are a result of the monetary system itself. Hence, two questions are in the focal point of my considerations:

- Firstly, how can the need for economic growth be diminished to a healthy proportion and the justice of distribution be restored?

- Secondly, what means are available in order to practically implement such objectives?

First, however, a few basic thoughts, without which neither the problem, nor the solution, nor the proposition for practical implementation or the taboo which the subject presents would be comprehensible.

A constructional flaw in the system: The interest

The money that we are dealing with on a daily basis serves two conflicting purposes: on one hand it functions as a universal means of exchange, being thereby one of the most ingenious inventions of mankind and the condition for a functional division of labour, i.e. the foundation of each civilisation. On the other hand it could be stockpiled, and in this capacity it may impede exchange. If one person has a sack of apples and another one has money, the apples are bound to rot within a few months, whereas money will retain its value. The imperishability and the so-called “joker” attribute of money (something that may be exchanged for anything) present the preconditions for the interest, which a money owner can charge, without having to lift a finger. The matter of course, by which we nowadays approve of the receipt and payment of interest, is based on three fundamental fallacies.

1st fallacy: Money can grow quantitatively over an extended period of time

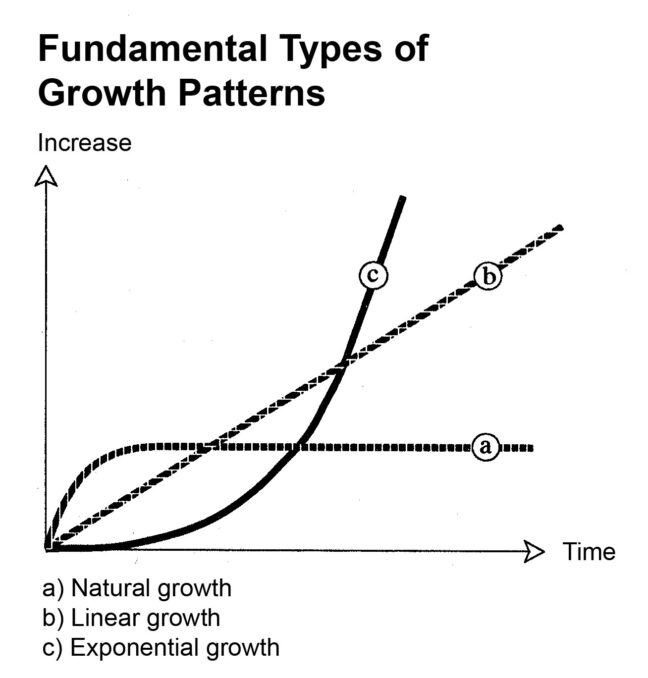

It is important to distinguish between three different types of growth patterns that have entirely different consequences:

- The first pattern, pursued in the physical domain by our human body, as well as plants and animals, could be described as “natural growth”: we grow quickly in the early phases of our life, then slower, until physical growth eventually ceases, usually once an optimal height has been attained, around the age of 21. From this point on, that is to say during the longest period of our lives, the changes that occur in us and in our subsystems are almost exclusively of qualitative nature, and no longer quantitative. The biologists represent this type of growth as a curve, referred to as a “growth chart”. I would like to call it the “qualitative growth curve” (see diagram on the right).

- The second growth pattern is mechanical or “linear” growth: if several machines are employed, these will produce more goods. This form of growth is of little relevance to my further analysis. Nonetheless, it should be pointed out that even such a continuous performance gain can in the long run not be sustained on our limited planet.

- By contrast, for my further line of thought the understanding of so called “exponential growth”, which could be referred to as the exact opposite of natural growth, is particularly significant. Here the growth curve starts off flat, then becomes steeper and eventually turns into an almost perpendicular line.

Exponential growth usually ends with the death of the organism in which it occurs.

In nature as well as in the human body such growth usually signifies disease. For instance, cancer follows an exponential growth pattern: at first it grows slowly. One cell turns into 2, then 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512 etc. It grows increasingly fast. When at last the disease is discovered, it has often reached a stage, in which it can no longer be halted. Such an exponential growth usually ends with the death of the organism, in which it occurs – which usually implies the death of the “guest”, since the basis of life itself is eliminated through the annihilation of the “host”. The lack of understanding for the problems of such a form of growth is the most consequential fallacy with regard to the function of money, since even financial assets double at regular intervals by way of interest and compound interest, that is to say they exhibit the properties of exponential growth. This explains why we in the past – at regular intervals and again at present – are experiencing serious problems with our monetary system, and why our society is dominated by a pathological compulsion for growth. Each participant, who seeks to escape this, is usually out of bounds. Hence, pleas to mankind or to individuals, such as the heads of international companies or politicians, have no benefits: As long as we do not change this system, the “constructional flaws of the monetary system” will remain the same.

The famous example of the Joseph-Pfennig shows that the interest is unable to work in the long run, and only for a short or intermediate period of time: if Joseph had invested a penny at the time of Jesus’ birth, and had been paid interest ever since at a rate of five percent on average, the value of this penny would by the year 2000, calculated by the price of gold at the time, have reached beyond 500 billion pellets equating the weight of this planet in gold. This goes to show that a persistent accumulation of interest, despite being mathematically calculable, is virtually impossible, and that is why interest as we know it, is unable to function in the long run.

One could say that the principle of interest and compound interest behaves like a cancer in our economic system and thereby also in our social “organism”. Sooner or later, the system is bound to collapse. The time period leading up to collapse for interest rates between 20 – 40 percent, as we know it from the past in Latin America, corresponds, based on experience, to 10 – 15 years, and for interest rates between 5 – 10 per cent, as is common in Europe, to approximately 50 – 60 years. And that is exactly the moment that we now have reached – more than sixty years after the end of WWII.

2nd fallacy: We only pay interest, when we borrow money

The second fallacy consists in the presupposition, that we only pay interest, when borrowing money from a bank or elsewhere. This is certainly not the case, because each price paid for a product contains an interest component. I am speaking of the interest that the producers of commodities and services must pay to their own bank, in order to acquire and finance machines and appliances. In Germany, the interest percentage for waste collection, for instance, is around 12 percent, for the price of drinking water 38 percent and for rent in social housing it even reaches 77 percent. 40 percent interest or capital expenditure are contained on average in all prices for services and commodities needed in our daily lives (Creutz 1993/2001). If the interest was replaced by a different system, most of us could nearly double our income or respectively work less and still enjoy the same living standard.

3rd fallacy: The interest is a fair charge or bonus for the cession of liquidity

The third fallacy is the belief that the interest is by all means a fair charge since it is included to an equal extent for all people in all prices, and since everyone is also credited interest to their savings. Only a few understand to what extent the effect of interest and compound interest provides a constant redistribution of money, in flowing from those who must work for their income to those who let their money be “worked for” and thereby obtain their income effortlessly. But have you ever seen money “at work”? For each euro that anyone receives in interest someone else must have worked for an equivalent value; only then does our money receive and maintain its value.

The illusion of fair interest: Ten percent of the population earn the money that the vast majority lose through interest.

If one subdivides German households into ten equal groups, it becomes apparent that 80 percent of households are paying nearly twice as much interest by way of living costs than they gain through saving deposits, insurances or old-age benefits. For ten percent the revenues and expenditures even themselves out in terms of interest, and the remaining ten percent of the population earn the money lost by the large majority through interest. That is to say, upon closer inspection, the “justice” of retrieving interest via savings plans and financial investments turns out to be fallacious. Only when the interest value exceeds 500,000 euros do those who possess these assets profit from this system. In 2001 the sum redistributed daily via interest amounted to approx. one billion euros. While the majority of the population constantly loses money, banks, insurance companies and multinational corporations profit from the interest system.

In the power “game” of the market economy interest operates as follows: the teammates (financial agents) are punished with interest charges; the bad sports, who are able to keep the money in their pockets, are rewarded through interest-based income. This way interest generates – contrary to the often quoted claim to efficiency in an “efficiency-based society” – an effortless income. Furthermore, it induces a pathological (morbid) economic growth as well as an intensification of the uneven distribution of income.

The solution: A provision fee instead of interest

Since 1916 a solution, not only stunningly simple and elegant, but moreover practicable and comprehensible, has been at hand. The solution was first discovered and published by the German-Argentinean businessman Silvio Gesell (1949/1991).

Instead of paying interest Gesell proposes to charge a “provision fee”[2] to secure the flow of money: those who do not spend their money or make it available to others via their checking account, are “punished” with a small fee. In doing so, a stimulus is created – similarly to the current system – to hand the money down, by adding a different “debit” to cash (– 6%), money on current accounts (– 3%) and money placed in savings accounts (+/- 0%).

The retention of cash may be inhibited in various ways, for instance by providing a colour series for banknotes, which are devalued once a year (by 6%) or on a regular basis (monthly, by 0,5%) or marking them with expiration dates (similarly to alimentation). However, with an increase in cashless transactions (e.g. via chip cards, which are able to accommodate different payment functions) this will become increasingly simple. Whereas, money placed in a current account is subject to a smaller user fee (since, as is presently the case, it can at least partially be lent again by the bank), money in a savings’ account will not be debited, as it can be fully brought back into circulation. It can thus keep its value due to the fact that, without any exponentially growing demands on saving deposits, viewed over a longer period of time, even inflation can be escaped. Thereby, one of the many insecurities, induced by the system and affecting everyone, will at last be abolished.

The beneficiary will only be charged with a fee to cover the bank’s services and a risk premium, which are both fees that are currently included as a small percentage in each credit. In most cases they do not amount to more than 2 – 2.5% of the interest charges.

Money will thus largely be limited to its function as a means of exchange. However, it also serves as a stable storage of value. Current habits are hardly affected. If one has more money than needed, one brings it to the bank, which lends it out and thereby brings it into circulation. Hence, the user fee is omitted. That is to say, the incentive to save would still persist.

If the economy was hitherto dependent upon capital, money must now submit itself to the demands of the economy in order to avoid a loss.

What is most important about omissions in the new system is the exponentially growing demand regarding saving deposits and, thereby, the distortion of market development by way of unilateral accumulation of money through the hands of a few. If the economy was hitherto dependent upon capital, money must now submit itself to the demands of the economy in order to avoid a loss. That is to say, capital serves the people. A sustainable economy and prosperity thus becomes possible because the monetary system follows the natural growth curve, since this stops growing quantitatively once it reaches an optimal height and thereby generates qualitative growth.

A change such as this could imply the end of the need for economic growth for everyone; instead of more consumption, more quality of life; instead of more time shortage, more leisure. One may, perhaps, have time again for grandparents and children, for art and culture as an integral part of each human life. Perhaps we could experience an expansion in the educational system and welfare services, instead of cost reduction in both sectors. All of this because the pressure exerted by the money indebted to exponential growth towards the economy and towards people would be reduced.

The historical periods in which the circulation of money was safeguarded prove that people had a different relationship towards culture, art and time. The Bracteate money[3] of the High Middle Ages, for instance, was a foundation for the creation of the great cathedrals that we still admire today. The construction also served as a work provision programme, known from the outset that it would stretch over two hundred years until its completion. These days, money must be “amortised” within the course of three to five years, or else it will not even be invested. If we introduced this new monetary order, most would benefit from it, and nobody would have anything to lose. In connection with a reorganisation of land holdings, which places the surplus value of land at the disposal of children and their caretakers (cf. Kennedy, 2006), two of the main causes for poverty and the increasing divide between rich and poor could be abolished.

Part 2: Practical Examples of Complementary Currency Systems

Using two examples from Brazil, it shall now be clarified how such complementary sectoral monetary systems are in practice employed for different purposes:

- “Palmas” – a success story from Fortaleza (CE) – combines the concept of microcredit with that of a regional currency, which is issued interest-free by the cooperative Palmas Bank. [Read more…]

- “Saber” – a concept developed by Bernard Lietaer and Gibson Schwartz, commissioned by the Brazilian government – proposes a system of circulating education vouchers to support socially disadvantaged children and young people, funded through telephone charges [Read more…]

Translated from German by: Ana-Maria Hadji-Culea

Editing: Julie Ward

About the author

Notes

- Jump up ↑ Margrit Kennedy kindly provided this text for the publication on the credit project. It contains a summary of the more detailed presentation in her first book on the subject: “Geld ohne Zinsen und Inflation” [Interest and Inflation Free Money] (1st ed. 1991). The text was first published in a slightly expanded form in: Frank-M. Staemmler and Rolf Merten (eds.), “Aggression, Selbstbehauptung, Zivilcourage” [Aggression, Self-Assertion, Civil Courage], EHP 2006.

- Jump up ↑ He also uses the expression “demurrage”.

- Jump up ↑ Bracteates were a special form of coins in the 12th and 13th century. These were thin silver pennies printed on one side and sheeted with a diameter of up to five centimetres. They could easily be broken, hence the name. In 1189, the coinage prerogative of Emperor Barbarossa was accorded to local princes and bishops.